Dispatches from the Cold War

Asimov's SF 1982: A topless L. Ron Hubbard, a post-apocalyptic Postman, and telepathic lions make this issue a very mixed bag

November 1982: I’m in the first half of my sophomore year of high school, which would be the year I have Mrs. Suitor for English, where for the first time someone asks me to ghostwrite a paper for them (I decline). My membership in the Science Fiction Book Club is in full swing and each month I eagerly check the mail for my package of at least two books. I’ve finished the original Dune trilogy and moved on to Frank Herbert’s latest, God Emperor of Dune. In English class, we read A Canticle for Leibowitz, so science fiction seems welcome in the classroom.

Naturally, I do a book report on God Emperor of Dune. Mrs. Suitor dismisses it in class as something weird “about worm men” and so I never did something like that again.

Fables about nuclear apocalypse were fair game — the Cold War was colder than ever, after all — but everything else got you labeled as a nerd. Lesson taken.

Fortunately, while this experience did change my approach to self-selected book reports, it didn’t change my own personal love for science fiction (and horror, since I also gobbled those novels at a…ahem...frightening rate). I maintained my book club memberships and, of course, my subscriptions to Analog and Asimov’s.

Also by this time, I’d gathered a couple of rejection slips from Asimov’s. My first came the year before, in August 1981, from editor George H. Scithers for my first-ever submission, “The Space Scream.” It was a political thriller spanning from Earth to Saturn’s moons, featuring multiple characters and primarily set on an amazing, moon-orbiting space roller coaster known as the Space Scream.

All that in eight double-spaced, Courier-font pages. In my defense, the plot moved briskly, if nothing else.

Regardless, Scithers sent me a very nice little note, which I’ve always kept, answering my question about any minimum age for publishing in Asimov’s — at 13, this was very important for me to know — assuring me there was none. He let me know that “[f]or a beginning writer this is a good piece” and telling me, “Don’t try to tell too complicated a story in a short space.”

To this day, it’s probably the nicest rejection letter I’ve received — once I hit adulthood it seemed getting a response at all, even a short “no,” was the exception rather than the rule. Anyway, I collected a few others over the three years I submitted, most of which were pre-printed but with short hand-written notes from editors telling me they were overbought but to please submit again. I received a couple of those notes from Kathleen Moloney, who took over from Scithers and was the editor of the Asimov’s issue we’re about to dive into.

Science fiction magazines were some of the most supportive communities I ever dealt with as a writer.

Front Matter

Let’s start with a personal bete noire, the opening editor’s note — in this case “Up Front” — shilling for all the content in the magazine you’re about to read. I hate, truly hate, these things. First, they are a waste of a page that could be used for other content. Second, I know what’s in the magazine because I’ve seen the cover and I’ve seen the table of contents. As a reader, I’m going to assume the editor really likes the stories and articles in a magazine because they’re the ones who bought and published them in the first place.

I don’t hold this personally against the Moloney, as these things were de rigeur back in the day. In fact, one of my proudest early moments as editor of Metro Weekly was killing off the editor’s intro letter.

Ah, great moments in history.

The magazine’s namesake, Isaac Asimov, contributes his monthly column, this time recounting his history as a poor immigrant who loved to read. He could read the magazines sold in his father’s New York City candy store, as long as he didn’t damage them because they couldn’t afford to keep them. Being a collector wasn’t an option.

Of course, Asimov went on to become one of the most published, re-published, and translated SF authors in history. As he tells it, space required him to eventually focus only on collecting his own published works in their myriad editions.

Hell of a flex.

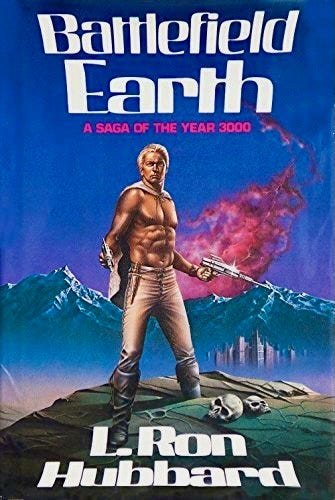

One more thing I want to deal with before diving into the issue proper: L. Ron Hubbard.

Right near the front of the magazine is an advertisement for his magnum opus (and John Travolta’s career killer), Battlefield Earth. I’d forgotten that it was actually published in 1981, as I didn’t get around to reading it until 1983 in the paperback version. Literary quality aside (it’s terrible), something immediately caught my eye in the ad.

Can you see it?

If you’re not familiar with the weighty and erudite visage of Scientology’s “founder” — I think “showrunner” might be a better term, he’s the Shonda Rimes of scam religions — take a close look at the blaster-wielding protagonist in the ad and compare that to Hubbard’s portrait.

Those pecs! Those abs!

So this sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole because that is not at all how I remember the cover of Battlefield Earth. I remember a big, beefy shirtless man with long, luxurious hair holding that blaster — not someone who looks like they just coordinated a seminar on best office management practices. I was a closeted gay kid in Kentucky, I remember pretty much every shirtless man I ever saw.

And I was right. The paperbook version did feature a lusciously locked slab of red-headed beefcake on the cover. Apparently, there was a bit of a stir among fans about the original cover not representing how the character was described in the book so they made the change and got the all Clear.

I guess it’s not all that surprising that L. Ron Hubbard was a Mary Sue. I’ll leave it at that, lest Scientology sues.

The Stories

“The Real Thing,” by Larry Niven

When a science fiction story includes a mention of the IRS in the first sentence, you can bet you’re reading someone from the right-wing leaning spectrum of SF authordom. Larry Niven is definitely one of those, judging by his military SF output alongside Jerry Pournelle, and possibly the most fascist-adjacent of the group. (Note: military SF is not by definition right-wing but when it’s written by Niven and Pournelle, it sure as hell is.)

I’m not joking — in my research I stumbled upon a news story about a Department of Homeland Security conference featuring a panel from SIGMA, a group of science fiction authors who felt themselves well-positioned to offer advice to the government on how things should be done.

During the discussion, Niven suggested spreading rumors in Latino communities that doctors were killing patients to steal their organs. The reason: to stop immigrants from accessing healthcare, which he was (wrongly) convinced was bankrupting hospitals.

“The problem [of hospitals going broke] is hugely exaggerated by illegal aliens who aren’t going to pay for anything anyway. … I know it may not be possible to use this solution, but it does work,” Niven said.

Naturally all this went down in 2008, a few years after Sept. 11 caused even moderately conservative writers to lose their goddamn minds and concurrent with the rise of Barack Obama, which pushed them over the edge for good.

Anyway, back to the story.

“The Real Thing” is essentially an early VR headset story, with a touch of Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember It for you Wholesale” (a.k.a. Total Recall) tossed in. In terms of Niven’s tech prediction, it’s hard to say because we have so far to go in this field. Apple Vision is probably the current best iteration of VR and it doesn’t even pretend to be full body sensory immersion. Guess I’ll have to revisit this in 20 years. Or not.

Overall, the story is just okay. Better than meh, but not notable or striking. Definitely not an example of New Wave science fiction. In fact, Niven is pretty much the antithesis of New Wave, even if he did write for one of the best of the acid-inspired Saturday morning 70s kids shows, Land of the Lost.

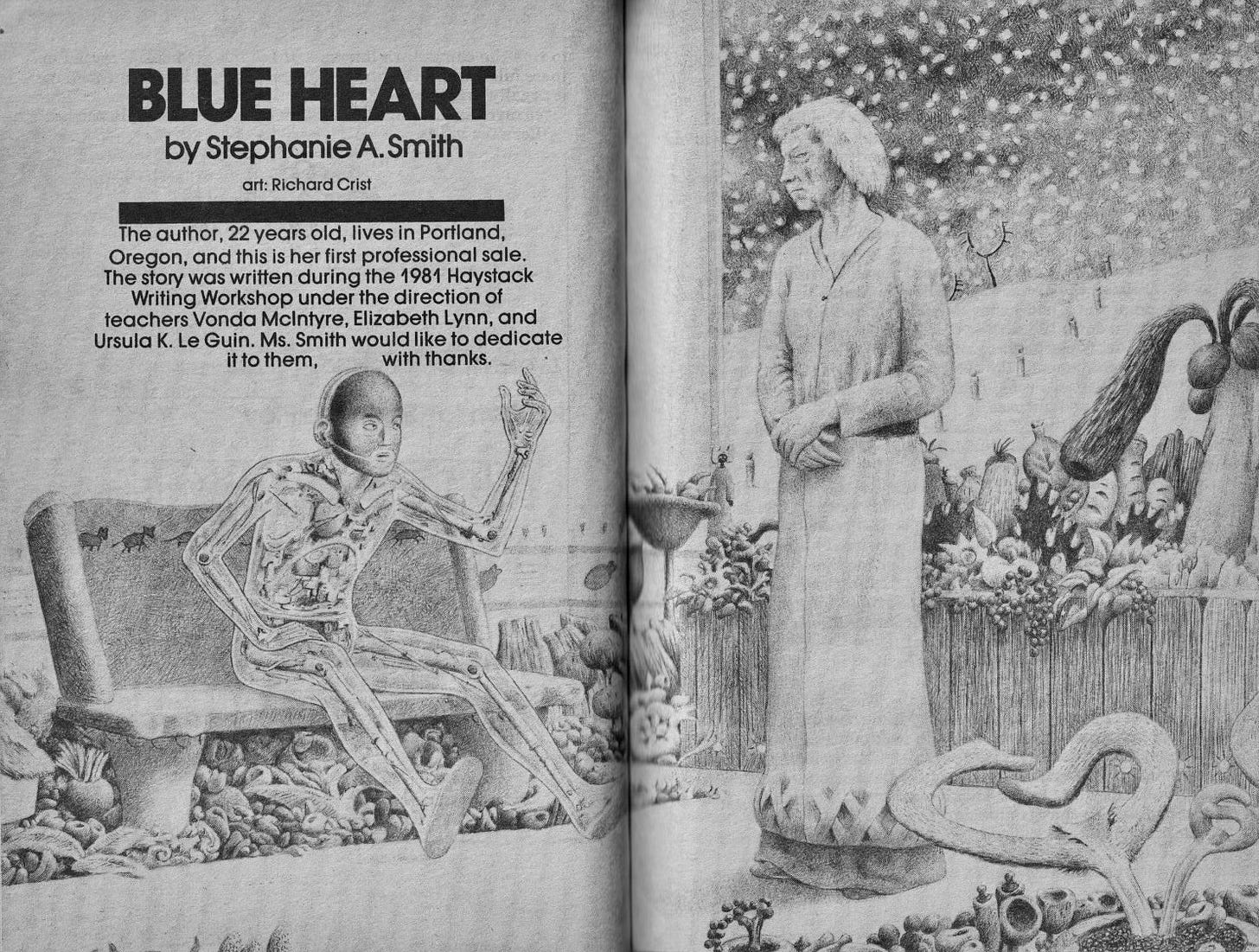

“Blue Heart,” by Stephanie A. Smith

As always, Asimov’s notes the age and number of sales for new writers — in this case, Stephanie Smith was 22 and this was her first sale. Information like this is why I was so obsessed with whether the magazine would accept at 13-year-old writer.

This story is pretty well written, to be expected since it came out of a writer’s workshop led by Ursula K. LeGuin and other prominent women authors. I don’t think it quite succeeds at being an unrequited love story at the edge of the vaguely defined universe. Smith hints at a lot, intriguingly, but very, very little is actually revealed. That kind of background world building can work if the story itself provides a strong framework; here I just don’t think it does.

The transference of mind — the central conflict is between a mechanical man whose mind was once biological and the woman he serves, whose aging is interfering with her ability to do her isolated job directing space traffic — is an old trope. That’s not a bad thing, it can be infinitely interesting to consider the ramifications. Here it’s just okay. The description of her working the web — a planetary system that works through direct mental connection — is beautifully described and presages some upcoming internet technology.

She was definitely paying attention to where the science was going and it didn’t lead her to Homeland Security conferences (she’s currently a professor and creative writing consultant, a much better career path). That’s a plus.

“Good Golly, Miss Molly,” by Stephen Bryan Bieler

And here we have a reductio ad absurdum on the availability of cheap and easy time travel, crossed with the “antics” of a compulsive gambler.

I really don’t care for these types of stories, which are essentially just stand-up jokes for science fiction nerds. But I must have loved them when I was a kid, because I have a couple of my own in my teen fiction folder — my big idea was turning a popular TV commercial into a horror vignette. It was rejected and for that I’m retroactively glad.

If you do like this sort of stuff, I suppose it’s fine and I’m not going yuck your yum. It’s definitely better than all those pun-based poems and crap in the last issue. But either this story is taking the place of something better or what was left in the slush pile was truly terrible.

“Closing Time,” by George R.R. Martin

This is you do a wordplay story.

If you’re at all familiar with his written work (and haven’t lost your mind over Winds of Winter), you know that George R.R. Martin has an extensive back history of good, solid science fiction and fantasy work stretching back through the 1970s. He was already a bit of a fixture by the time 1982 rolled around and this story shows why.

It also shows that Martin has a good sense of humor, one that doesn’t come through in such dire dramas as Game of Thrones (the books, not the show).

This is a story with a punchline, which historically for this magazine has been bad news. Those stories are typically written backwards from a punchline, badly. Martin, however, is writing forwards — moving toward exactly where he wants to go, but taking the time to create some interesting characters who provide humor that’s independent from those ending lines.

The story feels like its going in one direction before taking a big swerve at the end. If you pay attention — and know a little something about 1970s automobiles — you may figure out the ending right before it happens. That’s a good feeling and it takes a deft writer to elicit it.

Even though this story is 42 years old and not currently anthologized in active print, I’m not going to spoil it because it’s worth tracking down. It’s possible to find online, though one that I found I’m not going to link to because 1) the copyright issue makes it a bit suss, and 2) that transcription is interspersed with notes attempting to tie aspects of the story into A Song of Ice and Fire, which, good god that is tedious, don’t do that. Let the funny story just be a funny story.

I wish Martin wasn’t in Winds of Winter hell. He deserves better.

“Grace,” by Richard Bowker

Contrary to popular belief, science fiction and religion do mix — at least when it comes to matters of faith versus technology, or other interesting ways that belief systems come into conflict. One of the earliest stories I read that covered this territory was Arther C. Clarke’s “The Star.” In that, a priest on an interstellar exploration mission discovers that the star that guided the wise men to the birth of Christ was actually a supernova that wiped out an alien civilization.

The story is from 1955, so give me a break about spoilers.

Anyway, even as a kid I got how powerful that revelation was. I was still going to church at that time, so maybe that helped it hit a little harder. These days my agnosticism or atheism (I’m one or the other depending on the day and my mood) makes the story more of an intellectual exercise than an examination of personal faith.

“Grace” attempts to be part of that tradition but in a specifically Catholic kind of way. Now, I’m not a Catholic and I’m sure there are subtleties to the literature of Catholicism I sometimes miss. I don’t think I’m missing anything here as it comes across as pretty obvious. The narrator is captain and sole crew of an interstellar resupply route, servicing a world where the only human occupant is a phenomenally wealthy woman who has turned away from human civilization to care for members of a near-sentient, rodent like, bipedal race who are dying out from disease and starvation.

The captain spins three conjectures about why the woman has chosen to do this. She provides no answer on her own, only noting sadly in response to his question that a person who wants to be a saint cannot be a saint. She dies, leaving her “flock” to the perils of nature. The captain, obsessed with her decision, ultimately decides to take her place, offering three different versions of that decision, ranging from altruistic to vengeful.

I actually like stories of grappling with faith, both in science fiction and literature in general (stay tuned for Flannery O’Connor content, coming next month). This, though, doesn’t do it for me. It’s interesting but the narrator is incredibly unlikable and the meaning of the resolution is murky. Perhaps that’s the point.

“The Devil at the Door,” by Steve Vance

I’ll be honest: I hated this story. And I’m not here to cruelly beat on writers for work they did forty-something years ago. So, if you want entertaining and hilarious fantasy, go read Terry Pratchett. Otherwise, just move on, like I’m doing here.

“Lioncel,” by Madeiline E. Robins

Just as in the previous issue I covered, here’s an animal horror story masquerading as SF, in the grand tradition of Stephen King (so much of his stuff is science fiction and he’s another one coming up on my content list, he’s inevitable). Here, it’s a tale of genetically altered lions — lioncels — produced and offered commercially to be companions for animal lovers or prey for animal hunters.

Oh, and two angry ones have just formed a telepathic link with the handler tasked with delivering them to their certain death at a hunting reservation in Africa.

Despite a very clunky opening, “Lioncel” does boast a subtext of caring for the natural world, which has been a good theme to see through the issues we’ve covered so far. And, in terms of prediction, well, we may not be at exactly this point in custom genetics but we’ll be there soon. Through centuries of domestication and breeding, humans already created genetically designer creatures — have you seen a labradoodle? No way humans aren’t going to keep speeding that process up.

One problem with this story is the vague nature of the setting. Hints of the broader world are there but don’t tell enough to get a handle on what may be out there. Is it a corporate dystopia? Is it Randian self-reliance gone wild? Or is it just the same as it ever was? There’s no real answer. And that hurts the story because the heart of it is a lonely, isolated man choosing to maintain solitude and isolation over a chance at connection. That choice would read clearer with a better idea of its context.

“The Postman,” by David Brin

Now we arrive at the main event, the cover story that launched a series of novellas, that became a book, that became the movie that killed Kevin Costner’s career the first time: “The Postman,” by David Brin. I mean, it didn’t do as much damage to him as Battlefield Earth did to Travolta, but it was a deep wound.

And it’s too bad, because the source material is so good. From the beginning of the story, as the protagonist Gordon struggles to protect his belongings and his life from a gang of post-apocalyptic bandits, we get this:

“The soft world that had encouraged dreamers broke apart when he was seventeen. Long ago he realized his brand of persistent optimism had to be a form of hysterical insanity.”

Gordon is an oddly optimistic man for living in a world broken under the stresses of weaponized viruses, limited nuclear war, and good old American gun nuts. America almost made it through the plague and the bombs, per Gordon, but “the last straw had been this plague of survivalists.”

Feels relevant today!

With the east pummeled by fallout, failed crops, and paranoid violence, Gordon’s making his way west to Oregon. Along the way he earns room and board with the rare friendly — or at least neutral — settlement by performing bastardized versions of Shakespeare from memory.

While trying to survive his encounter with the bandits, he discovers a mail truck that crashed into the woods post-collapse, near perfectly preserved, and full of mail and — more importantly — a postman’s uniform to replace his stolen clothes.

At first he becomes a post-apocalyptic Johnny Bravo who just happens to fit the suit but who still inspires renewed hope in the first settlement he finds in Oregon. Then he finds himself in a less friendly situation and…

I’m not going to spoil this one, either. This story, whether the novel that came out later, or the novellas that led to the novel, are all pretty readily available. You should read them. I’d actually recommend going with the novel as this first novella is kind of rushed at the end, though still satisfying. I will say that I very much like that Gordon has mixed motives in how and why he becomes a postman. He’s not a selfless man but neither is he a selfish one. He simply feels real.

There are a couple clunkers from the “that’s the way it was back then” file, such as meeting a “vaguely Oriental-looking girl.” And that’s the language white people used then — this is actually on the pleasant side of that racial language — so I think it deserves a pass.

Brin went on to write a lot of other great stuff. I’d highly recommend his Uplift series, which I re-visited during covid and thoroughly enjoyed. Overall, this was a great way to wrap up the stories for this issue. My fingers are crossed our upcoming subjects also stick the landing.

Next time: We take a trip through one of the last survivors from the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Amazing Science Fiction Stories (September 1981), with Roger Zelazny, Harlan Ellison, Robert Silverberg, and more.

The Battlefield Earth ad is giving Donald Trump NFTs.